Monday, May 4, 2009

snowball

Of the topics that affected me the most, I think the one that has still left me thinking about it more often than not is the question of how my work needs to be political or... should it be political. This semester Subhankar Banjeree and his work made an impression on me in ways few others have. It wasn't that I was blown away by the formalism of his compositions and conceptual framework. It was that I felt compelled to analyze what was really going on, the political nature of work like that, and his intentions as an artist. I'm still in awe of how someone quits a career to take up a hobby full time, ends up in the smithsonian and then, gets famous for work that the smithsonian didn't really want. There's something to be said for that.

On another note, I was listening to NPR this weekend and there was this story about a bird named Snowball that learned how to dance to the Backstreet Boys. They tested him and he could adjust his dancing to the tempo of the music if it changed. So, this has further implications... like doing more experiments with birds (cockatoos) to determine how exactly it is that human brains evolved in the ways they did. We can't ethically deprive babies of human interaction for the first years of their life but we can do those type of experiments with birds. And we can make conclusions from those experiments about how it is that a brain learns to mimic sound and make movement that's coordinated with that sound. So far, according to the NPR story, only elephants, birds and humans are capable of doing that. But anyway here's the video. I don't like backstreet boys so much so I'm gonna put up the Queen version :)

Saturday, April 25, 2009

after nature landscapes

I think I'm a little obsessed by landscapes with a certain "after nature" quality to them. It might come from my fascination with post-apocalyptic movies or sci-fi movies in general. One of the greatest films of this category is one that still haunts me, Planet of the Apes.

Planet of the Apes illustrates the pyramid scheme of nature that humans have always been at the top of. What if it was inverted? What if apes passed us by? What if plants passed us by? I think that's the question that an image like William Christenberry's stirs...

William Christenberry, Kudzu with Storm Cloud, near Akron, Alabama, 1981.

William Christenberry, Kudzu with Storm Cloud, near Akron, Alabama, 1981.But this control over nature that we think we might possess is really just a false sense of security anyway. Example A - the events of the past week in Mexico and the spread of an A (H1N1) virus to the rest of the world (this virus is almost identical to the one that started the Spanish pandemic of 1918 that killed between 20 and 100 million people worldwide). This virus probably won't be as deadly as the Spanish plague but what it does is scarry. The virus originates in animals; first birds, then pigs, and it crosses back and forth for a while until it hits humans. When it hits humans, it strikes their immune system inciting what is called a cytokine storm where the body's immune system fights back so hard that it actually collapses. And it doesn't just strike kids and old people who are usually susceptible to illness; it strikes healthy, young and mature adults who's immune systems are actually tougher. Their systems try to fight the virus with all they can and that can turn into a fatal reaction. Pretty freaky.

So, I think this control over nature we think we possess isn't really control. I don't think after nature particularly exists in the ways it'd be neat to think that it exists (the Jetsons).

It'd be neat to think about it this way. A fantastic sky city where the horrible part of nature (the earth) is completely obstructed by clouds. A similar utopic-post-nature vision is setup in WALL-E where the humans have abandoned earth and are living in a space-cruise boat. Both plots assume that humans get to a point where nature can simply be removed from the equation. A point where humans ascend to the highest point they can and don't have any reason to come back down.

I'm not gonna suppose that happens. I'm not gonna suppose that humans will ever get to a point or are already at the point where we are living post-naturally. We are in a full-contact sport with nature. It's ongoing and neither side could be considered winning. For every step of progress we make to combat the force of nature (levies, vaccinations, fire proofing, concrete, etc.) nature seems to always be one step ahead. I'd like to see art that assumes that we aren't winning this war with nature (maybe Eirik Johnson?). Like Christenberry's (even though he didn't really intend it to be in a post-apocalyptic show), work that has nature winning as the default.

What's really weird (I think the show kind of remarks on it) is to think about how Christenberry's images could actually be the backdrop for Cormac McCarthy's novel The Road. A story about a man and his son who have to walk across a deserted United States in search of civilization and on the run from cannibals.

Monday, April 20, 2009

The Vision of Herzog

A scene from Heart of Glass, 1976

The plot for Heart of Glass is set in an 18th century German town that contains a factory which produces a brilliantly colored "ruby glass." When the master glass blower dies, the secret for producing the ruby glass is lost, and the townspeople go crazy. The main character is Hias, a "seer" from the hills, who speaks prophecy to the townspeople. The clip I posted is the "vision sequence" that Hiar has while watching a waterfall. I think this clip incorporates a lot about what Singer is writing about and what Herzog is trying to achieve.

Singer states of Herzog's vision: "Herzog seems to presume a need for making desire itself the definitive limit of the human. This crisis of representation is faced by Herzog in his often cited statement that "we live in a society that has no adequate images" (p. 189).

The quote seems to back up what I believe is a Kantian and Romantic notion of the Sublime by Herzog. The article defines Kantian as "an object (of nature) the representation of which determines the consciousness to think the unattainability of nature as a sensory representation of ideas." Meaning: "the sublime is the mind's limit, a threshold of transcendent knowledge"(p. 185). Singer goes on to explain further that in the Kantian sublime, Nature will inspire the imagination to image its own failure and by that, the imagination can't really come up with anything else to explain what it is seeing.

I'm still a little lost by this but it is starting to make sense. This idea of the sublime is very related to the ideas that I understand about Romanticism which are at their core, part of the German national identity. An identity that is eternally searching for that inner-longing that can be satisfied by a sublime landscape. A landscape such that when one encounters it, one will have an experience that can't really be described using language. I think, photography is the language though that can describe it. And I think Herzog mastered it at an early age.

The most recent film by Herzog, Encounters at The End of The World, looks curiously at the continent of Antarctica through a lens that engages science through an understanding of Art. In the article by William Fox, Terra Antarctica, the occurrence of Fata Morgana is explained and I only wish Herzog could have captured this in his film. I can only imagine what it must look like, but by Fox's description alone, I think it could be an essential part of what Herzog wants to examine. What is in the film though is quite spectacular. The volcano stuff is the best!

After looking up some artists that work in Antarctica, Xavier Cortada was the one that caught me as the most interesting. Using painting and sculpture, Cortada examines how we come in contact with and describe the desert continent. Here's an article about Cortada working within the intersection of Art and Science in Antarctica.

Monday, April 13, 2009

new(er) topographics

On page 15 of the article in the second paragraph, Adams writes about the act of photographing landscapes...

"Most photographers are people of intense enthusiasms whose work involves many choices - to brake the car, grab the yellow instead of the green filter, wait out the cloud, and, at the second everything looks inexplicably right, to release the shutter. Behind these decisions stands the photographer's individual framework of recollections and meditations about the way he perceived that place or places like it before."

Every time I read this paragraph I am immediately transported to a place where I photographed, to a moment where I made a decision. Adams is writing a lot about power and control and beauty but what concerns me most when I'm wherever I am photographing is the loss of control of all of these things. It's a strange feeling.

Timber salvage on ridge at eastern limit of blast zone. Clearwater Creek Valley, ten miles northeast of Mount St. Helens, Washington, 1983, Frank Gohlke

Timber salvage on ridge at eastern limit of blast zone. Clearwater Creek Valley, ten miles northeast of Mount St. Helens, Washington, 1983, Frank GohlkeWhat is always brought up with Adams is his critique of the advancing suburbs of Denver and his disappointment for the behavior of people toward nature. I won't deny that critique. But what I think is important today about taking landscape photos is vastly different from why it was important to take landscape photos in Denver in the late 60s and early 70s.

Since we already have this critique, when I make a picture like this, it is not to simply mimic Robert Adams.

To deny the part of this picture about the houses creeping through the plains might be naive of me but I think landscape photographers of late have had something else on their mind; It's history, memory, form, and something more enigmatic.

I'm really attracted to form. Man-made landscapes that use form to their advantage and that are built suitable to their surroundings are ok by me. I don't feel like they are intrusive or rape the land somehow of it's pristine nature. I believe there is a point where development can only go so far and that over development is totally problematic and systemic to America, especially the West. However, I think new photographers (me and Newhall at least) want to tweak something else out from the landscapes.

I think what's important to me when I'm photographing - is remembering the sublime. Remembering those moments in those places where I didn't exactly know if I wanted to photograph but then I decided to make a picture about being in that place. If it's a good picture, the formal elements will be right, but there will also be some other element, an element of chance or risk that I took that ultimately pays off.

I keep thinking about that; how memories deeply effect photographers. How experiences like driving, back and forth between St. Louis and Janesville, WI four times a year for the first 20 years of my life or having a digging hole in my backyard that mimicked the topography of Missouri in miniature scale - these things are still in my photographs even though most of the time the reason I'm inclined to take a photo at a certain place has to do with the subject of the project I'm working on, I still seem to take some element from my past and put it in the picture. This is what I think Robert Adams meant when he said "Making photographs has to be, then, a personal matter; when it is not, the results are not persuasive. "

Monday, April 6, 2009

ANWR

While reading both articles, I thought about how my own subject is closely related to Banerjee's and how although his project wasn't politically didactic from the images alone, it became that way because of how subversive the text and images were together . It amazes me how controversial these photos became because of the political nature of the text that accompanied them in the Smithsonian exhibition and the accompanying catalog. What happened wreaks of censorship and is unsurprising given the records and clout of the Bush administration and Senator Ted Stevens (R) of Alaska.

But still, I have a few updated questions for Subhankar given that Alaska is still such a hot topic in today's political world and environmental movement. Such as what was your reaction when Sarah Palin used "drill baby drill!" as a political whip? Did it spur something in you to push harder or push back? I would have severe doubts about the effectiveness of a project I was taking on given that the GOP was on the other side ready to pounce on me the moment it threatened them. Fortunately for Subhankar, he has firmly established a base to exhibit work and has already been in the midst of political debate for the past six years. Making and exhibiting work probably isn't a question of motivation for Subhankar. He did up and out quit a job at Boeing that he had worked his life for. But the problem that still seems to persist is how to position the work to be most effective given that the issues of ANWR are still being debated.

The article by Finis Dunaway gave me this idea. Dunaway writes about how even though the land and animals of Alaska are far removed from the land of the "lower 48" that they are directly affected by the decisions made by corporations and government and that the results can actually be measured through the close observation of the land. That is exactly what Subhankar is doing. He is the relay, the conduit by which the affects of the decisions that have been made can be measured. It blows my mind a little. It's just like the icebergs melting, just like the polar bears that have to swim further and further to find land. The responsibility then becomes ours, the viewers and the citizens of the U.S. to act on and make sure that our government is being held accountable.

I searched ANWR on Google images and the top results were maps conveying the physical size of ANWR in Alaska to the size of the lower 48.

I don't think this is a coincidence. The right wing has taken two positions that favor using the least amount of intellect to determine the right course of action. One, that the physical size of ANWR means that it's ok to destroy it because generally speaking, it's only the size of Wisconsin. And two, the landscape is so bleak and white that it's aesthetic value is equivalent to that of copy paper.

Fortunately, in the Google results alongside these maps are Subhankar's photographs.

Monday, March 30, 2009

I have to post this...

fascinations with modernism

James Howard Kunstler gave the keynote address at the conference aptly titled Sprawl and his observations about the city mirrored my own. They centered around the point that even though Dallas was supposed to be a bustling and interconnected city of commerce and industry, its infrastructure and architecture is so flawed that you have to walk 5 blocks from the Hotel to get a stick of gum. Sidewalks will dead-end at an alarming rate and more often will lead you into the middle of an intersection that lacks a crosswalk.

The architecture, like the street design, is just as uncoordinated and lacks any kind of interconnected style. On Sunday morning I walked by a 70-story-skyscraper that was totally locked up and forsaken of any human activity. How a building of this size remains totally dormant, sucking energy on the weekend free of any productive activity really bothers me.

I did appreciate the little thought that went into designing the west end center where the few restaurants and night life exist simultaneously but the rest of the city is in serious need of a neighborhood-kind-of-love that is all too easy to find in a city like Chicago.

While the design of the city and its architecture lacks any kind of integration or sympathy towards humans, the architecture does fascinate the hell out of me. I saw quite a few modernist and post modernist buildings that looked like they could quite easily be used for prisons or maybe Dick Cheney's office.

After reading the article "Buckminster Fuller: Starting with the Universe" and looking up a little information on the man himself, I think Dallas could benefit tremendously from even one implementation of Fuller's amazing ingenuities or philosophies.

I had the opportunity while growing up to actually see and participate in Bucky Fuller-inspired architecture, that is the Climatron in the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis, Missouri.

The Climatron

The Climatron plan for the Climatron

plan for the ClimatronNeedless to say, I'm anticipating the trip to the MCA tomorrow to see the Bucky Fuller exhibit and see the relevance of his ideas to the problems that face not only our urban centers but the sprawling suburbs of America. In the beginning of the article, Elizabeth Smith writes "still some have seen Fuller relevant as fodder for ideas about shifting interpretations of and unchartered terrains within modernism" (Smtih, 61). While I see how some might think this way, I think that it's important to keep Fuller's ideas in context and use them to explore new application; not as all-powerful solutions that were supposed to solve the problems of modern architecture instantly and forever. They are certainly futurist and require a discernment of design and application that when thoughtfully used could really help integrate and sustain life around them.

Monday, March 16, 2009

If I had a wilderness...

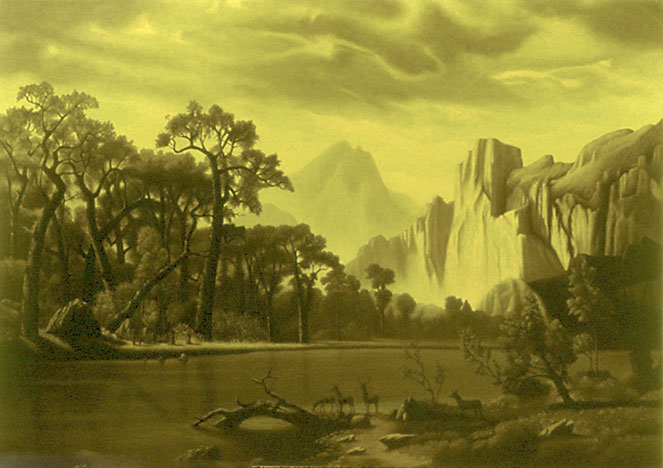

The painting uses the tropes of the Hudson River School in a way that seduces the viewer. Gifford almost convinces us that the Valley is supposed to look this way, its bowl shape contours with the mountain and a spectacular, unobstructed view is left. The tree stumps are left though, pretty obvious to us in a time when Eco-consciousness is firmly implanted into our brains. But not so obvious to people of the mid-19th century. None of the early Hudson River School painters ever left this sort of commentary. Until this point, it was more like this...

Cole's painting has less of an edge on it. A family has settled on the bank of a river, in a beautiful and pristine mountain valley. The people, their freedom and the opportunity to live in a land so overwhelmingly sublime was the promise of America and how the country came to define it's identity. Wilderness was the point by which they would define and name the new development. Wilderness symbolized freedom from religious persecution or more importantly, wilderness symbolized the taking over of religion by nature.

I watched Jeremiah Johnson last night. It just happened to be in my Netflix que. It's a movie by Sydney Pollack (whom I don't normally think of when I think of Westerns) and stars Robert Redford as the ultimate frontier-wilderness man. The story is a little predictable as Westerns go however, the moral of the film is a little different as Johnson struggles between killing and living peacefully with the Native Americans. He wants to live peacefully with them but they are savages and uncompromising. Nothing can stop them from brutally killing you and then taking your scalp.

The struggle with the Indians could be seen as a metaphor for how America conquered the Wilderness and "settled" the land-- systematically wiping them out and forcing them into reservations that are a fraction of the size of our National Parks. It is interesting to think about the names of the places where we live and how the towns, parks, roads and even picnic areas can have some link to a history or at least idea, that the place was once wilderness.

When I'm out shooting in the Midwest and I don't really have an agenda for the day, sometimes I'll pick a place with a name that sounds really good and wild-like thinking that the area will be scenic and ideal for my project. A lot of times the place will have the word "Falls" in it like Little Falls or Laughing Falls or whatever. More often than not, the place sucks. Whatever Falls referred to or meant when it was named, the place doesn't have that feature anymore. It somehow evaporated or was developed over. I can't say that this formula is true when I go out west. More often out there I'll find what I'm looking for when I search by a name (i.e. Red Rocks). But it really disappoints me when it happens. What were the settlers thinking when they named the place? Did they really think that the place looked like what they were calling it? Were they really conscious of how much Romanticism was intertwined with the language they were using?

Another part of this reading that got me thinking was the part about Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson and Ulysses S. Grant and their legacies on the land. I didn't really know the part about Grant establishing the first National Park in the Yellowstone territory- for some reason I always thought it was Roosevelt. The meaning of wilderness and settlement was to each of them, very different. Jackson and even Jefferson to an extent, really didn't use much discretion in the way of setting aside land that would be left "untouched" or undevelopled. They saw the vastness of the frontier as waiting to be developed and civilized, there's for the taking. Grant actually was the first one to say "hold on, wait a minute, we might go too far. We should probably save something before we ruin it." This is similar to how we marginalize and legislate land use today. A very small portion is rendered to park status and then everything else can be packaged and sold to developers and then those developers try to mimic the environment in their new development (I'm beginning to sound like Robert Adams).

I can easily get upset over this when I read about it. But I think the more proactive thing to do and the thing I've been attempting to do with my photographs is to ask questions. When is it too much? Aren't we co-existing with the land in good ways already? is it all bad? I'm sure it's not. I think many of my photos show ways in which we celebrate the land by establishing development. Ignoring the land really isn't an option. Development will ultimately happen in some capacity, so, why don't we try to reconcile and make the most out of it?

I'll end with this video I found on YouTube. It asks the question what would happen if we just give up and live out in the land? what happens then? can we actually become one with the wilderness? For the record, I think the man in the video is not my audience.

Oh, and I just read this in the nytimes about this noteworthy Gifford painting. I wonder who bought it...

Monday, March 9, 2009

the new politics of old land

But after I got scared, I got my idea for this week's blog and presentation. It occurred to me that the land that was so dried up and dead belonged to somebody, some farmer somewhere who was going to grow something on it in a few months and in another few months it would actually yield a crop that somebody or something might eat. This process has been going on for not hundreds of years but for thousands. We weren't the first ones to use this land. But we're the first to see it the way I did on Friday afternoon.

The plight of the Native Americans and the industrialization of the landscape that until Europeans arrived was "pristine" are two subjects that my work until recently hasn't touched upon. My images don't necessarily describe either subject in a literal sense. However, most images do have vast landscapes that at one time or another had Native American settlement or have been named for the Native Americans of that area.

My argument or position will be that people of European ancestry have disturbed and will inevitably destroy the landscape that Native Americans have coexisted with for the previous 12,000 years. My images will show the stages of "progress" by which the land has been consumed by development. Often the names of the places which are being developed are from the indigenous people of the area and serve as some kind of memorial to which the new people of the area can remember the old. There is usually minimal thought involved in relating the new development to the land and often what was left there by the Native Americans is dug up and then shoved into "archives" where they are organized by Western European art history standards.

The earliest European development is usually memorialized quite well with informative interpretive centers and plaques that describe the ordeal of the settlers who came upon the "savages" and had to kill them or at least move them in order to develop the land.

Heather, Starved Rock, 2008

Heather, Starved Rock, 2008Monday, March 2, 2009

if Porter and Adams had a son...

The thesis of the article is on page 7: "The environmental community's narrow definition of its self-interest leads to a kind of policy literalism that undermines its power." Literalism meaning in a way where environmentalists are fixed on achieving goals and milestones that are actually quite unachievable and actually set back the environmental movement because instead of small gains, the end result is no progress and the other side has rallied against your cause only to gain more solidarity. If I had read this article when it was written in 2004, I might have been more upset or more reactionary to it. However, Environmentalism and specific people (Al Gore, one of their main examples) have really rallied in the past few years and the movement has been spurred by a strengthening and a defining of the movement and its goals, victories by Democrats in elections and a weakening of the Republican base in every level of government. Now, that has yet to create a tide of change but I get the feeling that an awareness is present in the U.S. that wasn't there when this article was written 5 years ago.

The article by Shellenberger and Nordhaus acknowledges the misguided perceptions of Americans about environmentalists and gets to the root of the issue, how America is actually a lot more conservative than anyone on the left likes to admit. Also, how environmentalists suffer from a really bad case of group think - mainly "what we mean by 'the environment' - a category that reinforces the notions that a) the environment is a separate 'thing' and b) human beings are separate from and superior to the 'natural world'" (page 12). Instead of harnessing public perception and creating a base of issues from which the movement can start and then branch out, the movement has been focused on goals that directly take on industries where political clout and money are so dense, that no one and nothing has made a dent in them for the last 50 years.

The mistakes of groups and individuals are made clear by The Death of Environmentalism. Maybe it was the kick in the butt that Al Gore needed to take his slide show to the big screen. Shellenberger portrays Gore as one of the most guilty parties of the left, backing down in the 2000 election when they needed him most. But he did come back with An Inconvenient Truth and now I worry that he's beginning to loose it again. Maybe it's a case of crying wolf and we all turn a deaf ear and then it actually is a bear - or maybe just a wild dog... But anyway, my point is that this article focuses on something that I have become aware of since the rise of the environmental movement and that's how with the rise of extremists attitudes on both sides of the issue have lead to a stalemate for any real reform in the way America makes and uses its energy.

Bringing these issues to art is difficult for me. I'd like to think that my work isn't predictably environmental but talks about the environment and our footprint in a non-threatening sort of way. I would like to think that I'm an environmentally aware photographer. I realize the amount of chemicals and wasted paper I churn out and I always get the highest mileage vehicle I can get (which is usually the cheapest). But this stuff isn't directly in my art and it definitely isn't in my artist statement. If I do these things and make work that talks about land use and beauty and then don't take any step to show the work in a venue where the environment is talked about, am I really aware? what is the point?

I guess this brings me to the next article by Rebecca Solnit on Eliot Porter, Every Corner Is Alive. The article was really enlightening on the life and work of Porter and I feel like his work gets slighted by both the art and environmental communities because it doesn't clearly come out on either side. It isn't definitely conceptual, a rising movement when he did his major work, and it wasn't exactly the spark that was needed to spur the environmental movement. It did however, take a new view of landscape that the prevailing and preeminent landscape photographer, Ansel Adams, was lacking.

In looking at my own work, I think I'm positioned right in-between Porter and Adams. As Porter rarely incorporated evidence of human culture in his American work and Adams definitely did not, Solnit posits that the people in Porter's images from around the world were more integrated within their landscape as the "rootless" people of the U.S. were not. My argument with my own work has been that a) we are integrated with the land in the U.S. (in some poignant places) and b) this integration has come to defines us, so, we are not rootless anymore.

some images by me...

I think it is admirable for an artist to take dead aim at environmental issues in their work however, I think it might be a little naive to think that one's work, at this point, will singularly start a chain reaction that enables a shift in thinking and political movement. Burtynsky takes the middle road. Solnit states "facts themselves are political, since just to circulate the suppressed and obscured ones is a radical act" (Solnit 33). Burtynsky's work gives facts in clear, high-fi, large format detail. It's impossible to ignore or debate what is going on in his photos. If his work is political, and by Solnit's calculation it is, then Burtynsky has a responsibility to make sure his photos are seen in a context where the preservation and conservation of the environment is focused.

I just found this today... This is just one example of how the Environmentalism and Green Movement lately, have been a little out of whack in their rhetoric. Obama throws around "clean coal" in just about every stump speech. But what is "clean coal"? Does anyone really realize how dependent the U.S. is on coal and what the repercussions are of investing in coal technology instead of investing in solar, wind and other "sustainable" technology? The "clean coal" solution reminds me of the "low tar" and "light" cigarettes that came out in the 60s when they found out that cigarettes caused cancer. It's not really a solution. It's a way around a huge, systemic problem that will take more than a generation to fix.

Monday, February 23, 2009

oh yeah...

Sunday, February 22, 2009

big bird

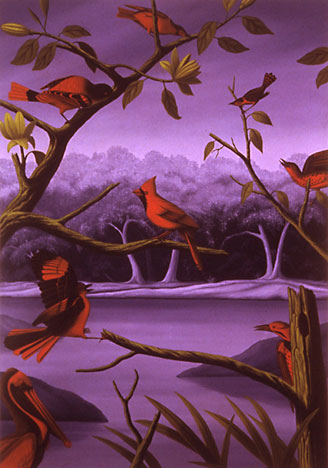

John Salvest's piece FLY, rearranges how we might interpret birds on a wire and does it in a rather obvious way, as if birds understood the English language or as if they knew the codes and translation for how to relate this message to humans via telephone wire. I think the piece is great for its play between coincidence and act of nature. Does it matter whether the birds possess the knowledge to achieve this act? The point is that they're communicating with us and we should be listening.

Lynching in the free state of California, 1999-2000, Peter Edlund

Lynching in the free state of California, 1999-2000, Peter Edlund State Birds of the Slave States, 2001, Peter Edlund

State Birds of the Slave States, 2001, Peter EdlundRoni Horn's work is really fascinating in how it explores identity (or mistaken identity). It reminds me of that song on Sesame Street, "one of these things is not like the other..." It sort of becomes a game to examine and figure out if the birds are different or if they're of the same species. The work plays with how humans assume or mistakenly assume a lot about what they're looking at. Horn's work doesn't really give us an answer and that's fine, it's better that way and it probably shouldn't. Birds don't give us answers either, the point is that we discover how we come to these assumptions and that we understand the differences between what looks to be two identical animals.

The diptychs are probably my favorite pieces in the article that I've found. My favorite piece that I haven't found online yet but swear I've seen in person is Michal Rovner's installation Of Mutual Interest where projections of flocks of birds fly from screen to screen on three walls in a square room. The piece is similar in Horn's in how the viewer examines and goes back and forth from point to point, examining relationships and what they know to what they're actually seeing.

Videos of nature and how we humans examine it and come to know it are probably my favoritest videos ever (Thank you Andy Goldsworthy!). So much so that I made a video piece of my own some four years ago in undergrad about my own relationship with landscape. In particular- the landscape surrounding the Missouri River and how by exploring it, I simultaneously coexist with it and interrupt it. This doesn't need to be critiqued but if it is whatever...

Sunday, February 15, 2009

biophilia; the plants, the animals and me.

The movie of Verne's novel along with the large aquarium that was in the living room during my childhood, allowed me to fantasize about a world that was so far away from the landlocked state of Missouri. On occasion, my family and I would visit The Fin Inn along the Mississippi in Alton, IL where they had huge aquariums of massive fish including tortoises that lived in the river.

The aquarium is fascinating in how it lets you view (in a somewhat unnatural way) the fish. It magnifies but flattens space. It's clear but condensed. It is living (algae and fish) but has fake elements of life (the plants). And the thing that keeps the algae and micro-organisms from taking over the whole tank is a machine that continually cleans the water through filtration. Occasionally, the fish die and a brief bathroom ceremony is held, but besides that and the short human intervention of feeding fish flakes, aquariums take on a life of their own.

Until thoroughly reading Shick's article, I think I have equated aquariums to an extension of science and never really thought of them as functioning in a way that creates art. But in discussing its history, Shick was able to convince me that "under-seascapes" are as much a part of the art world as they are the science world. In particular, the example of Matisse in Tahiti and how "the undersea light in the clear water was like 'a second sky' and by diving repeatedly.... taught himself to distinguish the quality of light in the two media."

In the last paragraph of the article Shick quotes Elaine Strosberg; "The teaching of science is not expected to emphasize aesthetic aspects... The arts and the sciences may increasingly have different homes and cultures, but they do not occur and must not be considered in isolation." I think this is the closest summary of my own thinking. There have been many times in making my own art that I come across a question that doesn't involve art at all but more often science and the question why? Art allows me to create and explore the question, but it doesn't necessarily give me an answer. Science ultimately, should be able to give an answer. It's almost as if for both to work as effectively as they should, they have to lean on each other to motivate and inspire. Which leads me to the next article...

Biophilia and the Conservation Ethic by Edward O. Wilson is a didactic article that at times left me feeling inspired and at other times, well, I really disagreed with it. One point in particular that I really disagreed with was about space exploration. Wilson states "'Biodiversity is the frontier of the future.' Humanity needs a vision of an expanding and unending future. This spiritual craving cannot be satisfied by the colonization of space. The other planets are inhospitable and immensely expensive to reach... The true frontier for humanity is life on earth,"

A little later in the article Wilson states how the loss of biodiversity is the most harmful part of the ongoing environmental despoliation and that "to the extent it is diminished, humanity will be poorer for all generations to come." Then he gives estimates about how much poorer we will all be because of the rapidly increasing rate at which the earth looses its species.

While I agree with the basic premise of Wilson's definition and application of biophilia, I can't help but totally disagree with the pessimistic and negative attitude that he has towards humans and how we're totally destroying the planet in a way that can never be reattained. I think this type of thinking is actually a little dated. Since the discovery of global warming and the activation of thinking about how to reverse it, I think humans for the most part are on the right track to overcoming a large part of the problems started by industrialization and a lack of forethought about the environment.

Though the problem about loosing species and biodiversity is troubling to me, I'm more inclined to think that this loss is in some ways natural and we should only do so much to slow it down or stop it. Did Wilson ever stop to think that maybe the extinction of some species might be more beneficial to preserving parts of nature that are sustainable and that maybe this is actually a part of evolution that has to take place? I mean lets be reasonable, the loss of species by man is detrimental and troubling, but the loss of species that never stood a chance of being saved because we had no knowledge of them ever existing- how are we supposed to overcome that or even gain some sort of control over that?

I'm not going to vent all my frustration out on this blog about what Wilson argued about space exploration- but I will vent a little.

He says biodiversity is the frontier of the future and humanity needs a vision of an expanding and unending future. Well, that is exactly what exploring space will answer. The beginning of time is literally somewhere in space waiting to be found. Somewhere in the middle of the universe, maybe a supermassive black hole and on the outer edges, the very outer limits of where matter exists, this is is where these "spiritual" cravings will be answered. NOT merely on Earth alone will these answers be found.

Humanity is a blip on the map of time. To be so focused as to solely and only look at our relationship with the world would ignore millions of years of history that have told the story of evolution, survival and extinction. I'd like to think that we would be so creative as to find ways to explore Earth and space at the same time. There's no reason, technology, money, ingenuity, etc. that we should have to choose one over the other. I think, (just as Shick, uses Parrish at the end his article) that we can and should examine both areas simultaneously as to elevate the understanding of both fields.

that said...

MAKE YOUR OWN PILLARS OF CREATION!

This photo is quite remarkable in its complexities of scale. It was taken by the Hubble space telescope and is a glimpse into a vastness of space that dwarfs anything we can relate to except maybe our own solar system.

"This eerie, dark structure, resembling an imaginary sea serpent's head, is a column of cool molecular hydrogen gas (two atoms of hydrogen in each molecule) and dust that is an incubator for new stars. The stars are embedded inside finger-like protrusions extending from the top of the nebula. Each 'fingertip' is somewhat larger than our own solar system." -from www.spacetelescope.org

"This eerie, dark structure, resembling an imaginary sea serpent's head, is a column of cool molecular hydrogen gas (two atoms of hydrogen in each molecule) and dust that is an incubator for new stars. The stars are embedded inside finger-like protrusions extending from the top of the nebula. Each 'fingertip' is somewhat larger than our own solar system." -from www.spacetelescope.orgMonday, February 9, 2009

gazing = good

the Pulitzer Foundation in St. Louis by Tadao Ando

the Pulitzer Foundation in St. Louis by Tadao AndoThe Darwinian view of nature, which Gessert is fond of, "implies radically new uses of art, to provide mirrors and models of evolution." And to achieve this he states that we need non-hierarchical models which affirm kinship. This brings to mind, not exactly a zoo, but something more like the Biosphere project where man is brought into the mix with the living organisms he impacts at a distance where what is affected can be measured and where man must think about and respond to relationships that are mutual.

The prospect of evolutionary art is a little sci-fi and intimidating to me. But I think a part of that is because of how I've been trained to think about my relationship with animals and other living things: I'm on top, they're on the bottom. But if this relationship is thought of as more mutual, maybe I would have less apprehension. And maybe if institutions would give a thought to exhibiting art outside of the visual media made of toxic materials realm (painting, sculpture, photography, the list goes on...) there would be greater steps made towards achieving a more cohabit-able and sustainable art world.

Gasp, our discussion is topical to current NPR...

The biological gaze by Evelyn Fox Keller fascinated me in a way that I haven't thought about science since I looked through a microscope sometime back in grade school. It brought back all those encounters I've had looking and at times prodding and dissecting nature; to explore and consequently learn about what I was seeing. I think I can say that what is written in the article has been wandering through my head (along with my cousin, (Dr. Ruzicka) who is a bio-geneticist and works on tomato plant roots) since I was a kid. There were numerous backyard experiments and gardens and holes made to grow and trap and look at what existed in my backyard. All were successful for what I learned, but I can't help but think about how many bees and lightning bugs (fireflies if you're not where I'm from) were killed for the knowledge that I have now...

Keller says that according to some philosophers of science "we do not actually see anything at all through a microscope." But this is because "they do not understand the nature of the activity of scientific observation." Keller goes on to explain that in this modern age scientists can and do "reach in and touch" what is under the microscope thereby 'making it real'. However by some measure, the organism whether it be a cytoplasm or chromosome is irrevocably affected by us gazing upon it because of the massive power needed to look so closely at an organism so not of our own scale.

Pre-19th Century, logic is wonderful in it's simplicity of thought. There aren't any variables or x factors, it is or it isn't. The pre-19th century way of seeing might be argued to have come back in vogue as reality TV, virtual reality and other new technology exploits what is called "real" but is actually a simulation of the real and not real at all.

Pre-19th Century, logic is wonderful in it's simplicity of thought. There aren't any variables or x factors, it is or it isn't. The pre-19th century way of seeing might be argued to have come back in vogue as reality TV, virtual reality and other new technology exploits what is called "real" but is actually a simulation of the real and not real at all.