Monday, February 23, 2009

oh yeah...

Sunday, February 22, 2009

big bird

John Salvest's piece FLY, rearranges how we might interpret birds on a wire and does it in a rather obvious way, as if birds understood the English language or as if they knew the codes and translation for how to relate this message to humans via telephone wire. I think the piece is great for its play between coincidence and act of nature. Does it matter whether the birds possess the knowledge to achieve this act? The point is that they're communicating with us and we should be listening.

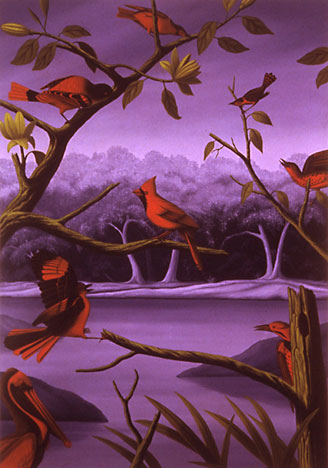

Lynching in the free state of California, 1999-2000, Peter Edlund

Lynching in the free state of California, 1999-2000, Peter Edlund State Birds of the Slave States, 2001, Peter Edlund

State Birds of the Slave States, 2001, Peter EdlundRoni Horn's work is really fascinating in how it explores identity (or mistaken identity). It reminds me of that song on Sesame Street, "one of these things is not like the other..." It sort of becomes a game to examine and figure out if the birds are different or if they're of the same species. The work plays with how humans assume or mistakenly assume a lot about what they're looking at. Horn's work doesn't really give us an answer and that's fine, it's better that way and it probably shouldn't. Birds don't give us answers either, the point is that we discover how we come to these assumptions and that we understand the differences between what looks to be two identical animals.

The diptychs are probably my favorite pieces in the article that I've found. My favorite piece that I haven't found online yet but swear I've seen in person is Michal Rovner's installation Of Mutual Interest where projections of flocks of birds fly from screen to screen on three walls in a square room. The piece is similar in Horn's in how the viewer examines and goes back and forth from point to point, examining relationships and what they know to what they're actually seeing.

Videos of nature and how we humans examine it and come to know it are probably my favoritest videos ever (Thank you Andy Goldsworthy!). So much so that I made a video piece of my own some four years ago in undergrad about my own relationship with landscape. In particular- the landscape surrounding the Missouri River and how by exploring it, I simultaneously coexist with it and interrupt it. This doesn't need to be critiqued but if it is whatever...

Sunday, February 15, 2009

biophilia; the plants, the animals and me.

The movie of Verne's novel along with the large aquarium that was in the living room during my childhood, allowed me to fantasize about a world that was so far away from the landlocked state of Missouri. On occasion, my family and I would visit The Fin Inn along the Mississippi in Alton, IL where they had huge aquariums of massive fish including tortoises that lived in the river.

The aquarium is fascinating in how it lets you view (in a somewhat unnatural way) the fish. It magnifies but flattens space. It's clear but condensed. It is living (algae and fish) but has fake elements of life (the plants). And the thing that keeps the algae and micro-organisms from taking over the whole tank is a machine that continually cleans the water through filtration. Occasionally, the fish die and a brief bathroom ceremony is held, but besides that and the short human intervention of feeding fish flakes, aquariums take on a life of their own.

Until thoroughly reading Shick's article, I think I have equated aquariums to an extension of science and never really thought of them as functioning in a way that creates art. But in discussing its history, Shick was able to convince me that "under-seascapes" are as much a part of the art world as they are the science world. In particular, the example of Matisse in Tahiti and how "the undersea light in the clear water was like 'a second sky' and by diving repeatedly.... taught himself to distinguish the quality of light in the two media."

In the last paragraph of the article Shick quotes Elaine Strosberg; "The teaching of science is not expected to emphasize aesthetic aspects... The arts and the sciences may increasingly have different homes and cultures, but they do not occur and must not be considered in isolation." I think this is the closest summary of my own thinking. There have been many times in making my own art that I come across a question that doesn't involve art at all but more often science and the question why? Art allows me to create and explore the question, but it doesn't necessarily give me an answer. Science ultimately, should be able to give an answer. It's almost as if for both to work as effectively as they should, they have to lean on each other to motivate and inspire. Which leads me to the next article...

Biophilia and the Conservation Ethic by Edward O. Wilson is a didactic article that at times left me feeling inspired and at other times, well, I really disagreed with it. One point in particular that I really disagreed with was about space exploration. Wilson states "'Biodiversity is the frontier of the future.' Humanity needs a vision of an expanding and unending future. This spiritual craving cannot be satisfied by the colonization of space. The other planets are inhospitable and immensely expensive to reach... The true frontier for humanity is life on earth,"

A little later in the article Wilson states how the loss of biodiversity is the most harmful part of the ongoing environmental despoliation and that "to the extent it is diminished, humanity will be poorer for all generations to come." Then he gives estimates about how much poorer we will all be because of the rapidly increasing rate at which the earth looses its species.

While I agree with the basic premise of Wilson's definition and application of biophilia, I can't help but totally disagree with the pessimistic and negative attitude that he has towards humans and how we're totally destroying the planet in a way that can never be reattained. I think this type of thinking is actually a little dated. Since the discovery of global warming and the activation of thinking about how to reverse it, I think humans for the most part are on the right track to overcoming a large part of the problems started by industrialization and a lack of forethought about the environment.

Though the problem about loosing species and biodiversity is troubling to me, I'm more inclined to think that this loss is in some ways natural and we should only do so much to slow it down or stop it. Did Wilson ever stop to think that maybe the extinction of some species might be more beneficial to preserving parts of nature that are sustainable and that maybe this is actually a part of evolution that has to take place? I mean lets be reasonable, the loss of species by man is detrimental and troubling, but the loss of species that never stood a chance of being saved because we had no knowledge of them ever existing- how are we supposed to overcome that or even gain some sort of control over that?

I'm not going to vent all my frustration out on this blog about what Wilson argued about space exploration- but I will vent a little.

He says biodiversity is the frontier of the future and humanity needs a vision of an expanding and unending future. Well, that is exactly what exploring space will answer. The beginning of time is literally somewhere in space waiting to be found. Somewhere in the middle of the universe, maybe a supermassive black hole and on the outer edges, the very outer limits of where matter exists, this is is where these "spiritual" cravings will be answered. NOT merely on Earth alone will these answers be found.

Humanity is a blip on the map of time. To be so focused as to solely and only look at our relationship with the world would ignore millions of years of history that have told the story of evolution, survival and extinction. I'd like to think that we would be so creative as to find ways to explore Earth and space at the same time. There's no reason, technology, money, ingenuity, etc. that we should have to choose one over the other. I think, (just as Shick, uses Parrish at the end his article) that we can and should examine both areas simultaneously as to elevate the understanding of both fields.

that said...

MAKE YOUR OWN PILLARS OF CREATION!

This photo is quite remarkable in its complexities of scale. It was taken by the Hubble space telescope and is a glimpse into a vastness of space that dwarfs anything we can relate to except maybe our own solar system.

"This eerie, dark structure, resembling an imaginary sea serpent's head, is a column of cool molecular hydrogen gas (two atoms of hydrogen in each molecule) and dust that is an incubator for new stars. The stars are embedded inside finger-like protrusions extending from the top of the nebula. Each 'fingertip' is somewhat larger than our own solar system." -from www.spacetelescope.org

"This eerie, dark structure, resembling an imaginary sea serpent's head, is a column of cool molecular hydrogen gas (two atoms of hydrogen in each molecule) and dust that is an incubator for new stars. The stars are embedded inside finger-like protrusions extending from the top of the nebula. Each 'fingertip' is somewhat larger than our own solar system." -from www.spacetelescope.orgMonday, February 9, 2009

gazing = good

the Pulitzer Foundation in St. Louis by Tadao Ando

the Pulitzer Foundation in St. Louis by Tadao AndoThe Darwinian view of nature, which Gessert is fond of, "implies radically new uses of art, to provide mirrors and models of evolution." And to achieve this he states that we need non-hierarchical models which affirm kinship. This brings to mind, not exactly a zoo, but something more like the Biosphere project where man is brought into the mix with the living organisms he impacts at a distance where what is affected can be measured and where man must think about and respond to relationships that are mutual.

The prospect of evolutionary art is a little sci-fi and intimidating to me. But I think a part of that is because of how I've been trained to think about my relationship with animals and other living things: I'm on top, they're on the bottom. But if this relationship is thought of as more mutual, maybe I would have less apprehension. And maybe if institutions would give a thought to exhibiting art outside of the visual media made of toxic materials realm (painting, sculpture, photography, the list goes on...) there would be greater steps made towards achieving a more cohabit-able and sustainable art world.

Gasp, our discussion is topical to current NPR...

The biological gaze by Evelyn Fox Keller fascinated me in a way that I haven't thought about science since I looked through a microscope sometime back in grade school. It brought back all those encounters I've had looking and at times prodding and dissecting nature; to explore and consequently learn about what I was seeing. I think I can say that what is written in the article has been wandering through my head (along with my cousin, (Dr. Ruzicka) who is a bio-geneticist and works on tomato plant roots) since I was a kid. There were numerous backyard experiments and gardens and holes made to grow and trap and look at what existed in my backyard. All were successful for what I learned, but I can't help but think about how many bees and lightning bugs (fireflies if you're not where I'm from) were killed for the knowledge that I have now...

Keller says that according to some philosophers of science "we do not actually see anything at all through a microscope." But this is because "they do not understand the nature of the activity of scientific observation." Keller goes on to explain that in this modern age scientists can and do "reach in and touch" what is under the microscope thereby 'making it real'. However by some measure, the organism whether it be a cytoplasm or chromosome is irrevocably affected by us gazing upon it because of the massive power needed to look so closely at an organism so not of our own scale.

Pre-19th Century, logic is wonderful in it's simplicity of thought. There aren't any variables or x factors, it is or it isn't. The pre-19th century way of seeing might be argued to have come back in vogue as reality TV, virtual reality and other new technology exploits what is called "real" but is actually a simulation of the real and not real at all.

Pre-19th Century, logic is wonderful in it's simplicity of thought. There aren't any variables or x factors, it is or it isn't. The pre-19th century way of seeing might be argued to have come back in vogue as reality TV, virtual reality and other new technology exploits what is called "real" but is actually a simulation of the real and not real at all.Sunday, February 1, 2009

my own wilderness

The first article from the Dictionary of the History of Ideas touches on the numerous definitions of the natural and how it's gone through several evolutions according with movements of science and religion. I found myself agreeing with most of them and understanding how now, in contemporary society, it is becoming more and more the social norm to understand that nature (not Nature) is something understandable and changeable.

My work lately has inadvertently incorporated several things that the first article touched on. For one, understanding what is natural and coexisting with it in a way where humans don't come to dominate or control but live with and within. Westerners, especially Americans in the 19th and 20th centuries have a particular preoccupation with dominating and conquering land that had millions of years of history before their arrival. It's only lately that I think western society has made advances in the way that we approach living with nature or coexisting with what is really wild. The designated areas of wild or less tamed land, can come close to what actually might be a wild and untouched earth. But I do feel that even by taking a simple measure of the Co2 in the air on top of a mountain that the earth can no longer be called completely wild.

The Practice of the Wild by Gary Snyder led me to think about all the occasions when I thought I was amongst the wild or was myself being wild. The article didn't change what I thought I was doing at the time. But now I think I understand a little more about where the idea for wild comes from.

As a human, I might not be completely wild, but the systems that make up my body, that allow me to live, are still inherently wild. They function instinctively and without my knowledge or consent. And though my mind doesn't function this way all the time I think I am aware of instances where I've let the wild in and tried to cherish it. For example, I let a wound heal on it's own while on a photo shoot two weeks ago. Though it was a small wound, there was something that made me feel like I was a part of something else, letting it do it's own thing and bleed and clot without my intervention.

In the last part of the article, Snyder refers to the etiquette of the wild world and how it requires "not only generosity but a good-humored toughness that cheerfully tolerates discomfort, an appreciation of everyone's fragility, and a certain modesty." He goes on to give examples of how emptying oneself to the point of having absolutely nothing leads to great insight and quotes a Tibetan saying that "the experience of emptiness engenders compassion."

It seems to me that we could all use this wisdom a little more living in a city like Chicago in a country like America. The city is very well insulated. But what comes close to actual wilderness isn't as far as one might think. I drove 10 hours to get to the Smoky Mountains and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan is about a 7 hour drive from Chicago. In the UP, I realized after driving on a one lane road for about 15 miles that I was in complete and total wilderness and that I hadn't seen a house or even a telephone pole for the past half an hour. I had zero cell phone reception and when I got out of the car all I could hear was the wind combing through the fir trees and the dead silence behind that. It freaked me out.

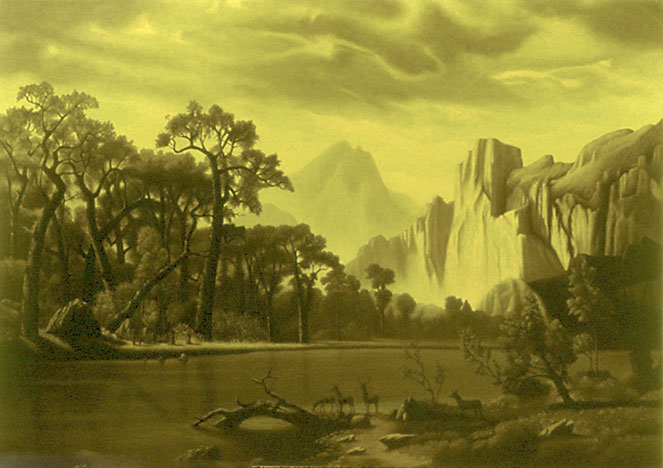

Albert Bierstadt

Albert BierstadtLooking Down Yosemite Valley, 1865

Bierstadt's painting shows what looks to be a pristine and majestic natural land that is yet to be conquered and fortified. He over indulged though in awe-inspiring, painterly techniques such as the use of the dramatic, raking light of dawn and mist or fog. Though his paintings are the quintessential example of a genre of painting that valued the land and took great strides to understand and explore, the paintings lack a certain depth that might examine why such views are so important to look at in the first place.